Modern scholarship largely attributes the general lack of representation of the natural world in Ancient Greek art to an ancient disregard for the natural world as well as an esteem for the civilized polis (city-state) setting above all else. The polis was the most basic and central unit of the political and social worlds of Ancient Greece. We think of cities today strictly as urban centers, but for the ancient Greeks, the concept of the polis was suggestive of an integrated whole: the urban center of the city as well as the extensive surrounding land. Such differing conceptions of the same general notion of a “city-state” gesture to, and leave much room for, modern misinterpretation of ancient actualities, especially as they are understood with relation to the natural environment.

This paper will explore the question: why is there a general lack of environmental representation in ancient Greek art? First, I will analyze ancient perspectives on the natural world in order to promote a more comprehensive understanding of how ancient Greeks perceived nature. Second, I will examine the representation of nature in the form of landscape elements in various artforms, with a focus on the artistic function of the employment of such elements. Finally, I will consider why there are so few representations of the natural world that survive in existence today, and draw attention to the inherently-limiting biases in modern interpretations of our already limited evidence. I will argue that the general lack of environmental representation in ancient Greek art is an issue of a lack of evidence, which is compounded by modern scholarship’s preconceived notions of nature in general, as well as what artistic representation of the natural world should look like.

Nature is a dominant theme in ancient thought, owing to the dramatic way it shaped civilization in very real and direct ways. In Hesiod’s epic Theogony, Hesoid presents himself as a shepherd whose inherently pastoral lifestyle is importantly in explicit contact with the natural world. This natural connection puts him in direct contact with the divine Muses whom he attributes the entire inspiration of his work to (Theog. 22). Thus the environment provides a direct avenue of communication to the otherwise inaccessible world of the divine. In a similar manner of thought, Plotinus characterized the natural world to be one of the important “launching points to the realm of mind” (Hornum, 1988). Plotinus focuses on universally appealing megaphenomena such as the sun, the stars, and life-sustaining waters as first-hand means of experiencing, and perhaps even transcending, alternative realms of being. These examples of ancient thought promote an aesthetic understanding of nature that seems to be “more about identification of aspects relevant or beneficial to oneself within it, and its potential to offer a culturally meaningful space to operate within” (Spencer, 22). We can extrapolate from these texts, a pattern in conceptualizing the natural world with respect to its function for humans. This notion of the environment having intrinsic function in regards to humanity can also be identified in the art historical record.

Minimal elements of landscapes, as opposed to landscapes in their entireties, are employed in ancient Greek art primarily with a limited function of representation. As Richard Neer points out, “Greek painting … always emphasized figures over their settings” (Neer, 221). Most basically, landscape elements functioned to locate a scene to be outdoors, in nature. Additionally, landscape elements could also serve as attributes of the gods and goddesses, make reference to a specific myth or hero, or symbolize abstract concepts that are not easily depicted, such as war, immortality, or victory. Natural settings were minimally expressed in accordance with “the Archaic and Classical impulse to inscribe the natural world,” which manifested itself in this minimalistic style by “carefully limiting human interaction with wild Nature” (Giesecke, 2007).

Depictions of the natural environment in Greek vase painting are highly uncommon, with specifically identifiable scenes being even more uncommon. The Attic red figure vase-style of the High Classical period is reflective of the ancient Greek impulse for inscribing nature, with the natural world carefully restrained in representation, framing depictions of human figures on vase scenes instead of overpowering them. The Lykaon Painter’s pelikē, a decorated storage jar ca. 440 BCE is an excellent example of the evolution of Greek environmental “landscape” painting (Figure 1). It shows Homer’s story of Odysseus’ journey to the Underworld and was described by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts Classical Antiquities Curator Lacey Caskey as being “of unusual, even startling interest” (Caskey, 1934). Thin, undulating lines of paint, spatially staggered on different levels characterize a rocky terrain. The scene is framed by tall, wispy reeds which function to indicate the scene’s proximity to a river. These two minimal natural features stage a specific wet and rocky environment that, in combination with the labeled figures, (Odysseus, Hermes, and the ghost of Elpenor) leave no doubt as to the location of the scene at the confluence of the Underworld’s rivers as described in Homer’s Odyssey.

Figure 1. Red-figure pelikē: drawing of Side A, Odysseus, Elpenor, and Hermes in the Underworld. The Lykaon Painter, c. 440 BCE. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, William Amory Gardner Fund, inv. no. 34.79.

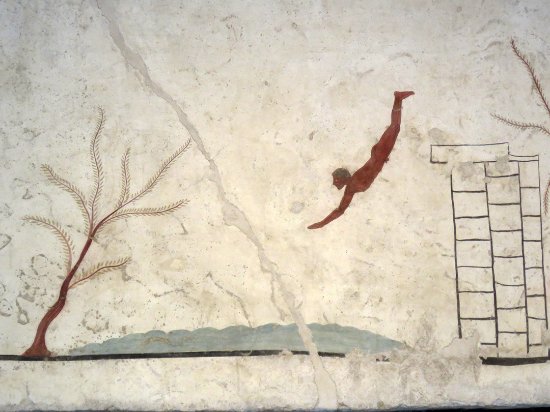

Another significant example of this minimalistic style of environmental representation is a fresco from the Tomba del Tuffatore, or Tomb of the Diver, dated to around 470 BCE (Figure 2). The necropolis the tomb is situated within is just 1.5 km south of the Greek city of Paestum in Magna Graecia. The painted ceiling, from which the tomb draws its name, shows a boy diving from a platform. The diver is “just a small element in a larger landscape,” (Neer, 221) framed by trees on either side. While the diver is the central focal point of the fresco that immediately attracts the viewer’s eye, it is interesting that the largest and most detailed images of the scene are the trees, with each leaf individually and painstakingly painted by the artist. For the ancient viewer, the scene might have been reminiscent of the nearby River Sele, functioning to evoke a more regional and thus personal connection to the fresco.

Figure 2. Fresco from the Tomb of the Diver. Paestum, c.470-469 BCE. National Museum of Paestum, Capaccio, Italy.

Turning now to the general lack of surviving archaeological evidence of environmental representation, I will begin by theorizing why this may be. In considering the artistic tendency to represent the natural world using paint as a medium, I am inclined to conceptualize the lack of evidence in connection to this preferred medium. Painting was the easiest way to show natural scenes; sculpture would have been much more difficult to render environmental imagery on, and probably more affective was the mere lack of demand for it, owing to a preference for human iconography. In comparison to other artforms of ancient Greece in existence today, a disproportionately less amount of paintings survive. It is crucial, first and foremost, that an absence of evidence should never be interpreted as evidence of absence. Fewer surviving paintings do not mean that painting was rare. Most surviving intact examples of painting are preserved in tombs, “but Greek tombs were usually simple; any extra resources tended to go toward a fancy marker” (Neer, 220). Paintings are in fact, much less likely to survive because they were usually painted on wood, which has since rotted away, or on walls of private or public buildings which have collapsed or been rebuilt.

Modern scholarship’s general failure to consider how our own perceptions of what environmental art looks like may serve to distort our understanding. A lack of representation of the natural world, as we expect it should be represented, has (not very thoughtfully) been interpreted as a total lack of representation. I recognize my own bias following from a similar line of thought; when I imagine environmental representation in art, I think of paintings that almost exclusively depict extremely detailed scenes of nature. Modern attitudes in general do not take very seriously the important and defining role that the environment plays in the maintenance and continuation of the very existence of humanity. We see this exemplified in the majority of society’s slow, or even failure to, uptake the reality of climate change and global warming, even when confronted with massive amounts of data and evidence documenting this climate crisis. Both ancient and modern thought share a similar theme of an inherent lack of agency in human interactions with the environment, as well as a perspective that the environment is something that needs to be conquered. Its worth considering the false implicit logic of these lines of thinking that may lead one to infer that because we do not respect the environment, the ancient Greeks surely didn’t either. We perceive an ancient bias, and accept it because it easily aligns with modern bias.

It seems to me then, that such modern biases inhibit the way in which we perceive ancient Greek representations of nature. The few representations of the natural world that survive, in combination with interpretive biases greatly limit our comprehension.The minimalist approach of the Greeks does not fit our conceptions of environmental art, thus we do not consider it as such. I would argue that ignoring any environmental aspect of a society is a failure to attempt to foster any deeper understanding of the society in question. How can we hope to understand a society if we do not also understand the many ways in which they interacted with the environment? This interpretation is especially problematic when it leads to related environmental factors being largely ignored in early studies and scholarship of the Greeks, as well as other past societies. Modern eyes do not understand the Greeks or their art as in connection with nature; this is a failure not of the Greeks to understand the natural world they inhabited, but on our behalf to properly rid ourselves of our own preconceived notions of what nature and natural representation should look like.

Bibliography:

- Caskey, L. D. 1934. “Odysseus and Elpenor in the Lower World.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts XXXII.191:40–44.

- Hesiod. Theogony; And, Works and Days. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

- Hornum, M. 1988. (ed.) Porphyry’s Launching-Points to the Realm of Mind. Grand Rapids: Phanes Press.

- Neer, Richard T. Greek Art and Archaeology: A New History, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. Thames & Hudson, 2012.

- Spencer, Diana. “Aesthetic, Sociological, and Exploitative Attitudes to Landscape in Greco-Roman Literature, Art, and Culture.” Oxford Handbooks Online. January 10, 2017. Oxford University Press.